May I Have Your Attention, Please?

Imagine for a moment: you are an author devoted to creating beautiful and inspiring books for children and young adults. Perhaps, somewhere in the back of your mind, you wonder if, someday, your work might be honored to receive a National Book Award. Then imagine that the impossible happens: You learn that your latest book was selected as a Finalist! You are barely over the shock and awe at your good fortune, and are settling into happy anticipation of the coming awards ceremony, where—who knows— your book might even be chosen the winner! Then, suddenly, all hell breaks loose. A book that was not selected is mistakenly announced to the world as a finalist. The aftermath is downright nightmarish.

Imagine for a moment: you are an author devoted to creating beautiful and inspiring books for children and young adults. Perhaps, somewhere in the back of your mind, you wonder if, someday, your work might be honored to receive a National Book Award. Then imagine that the impossible happens: You learn that your latest book was selected as a Finalist! You are barely over the shock and awe at your good fortune, and are settling into happy anticipation of the coming awards ceremony, where—who knows— your book might even be chosen the winner! Then, suddenly, all hell breaks loose. A book that was not selected is mistakenly announced to the world as a finalist. The aftermath is downright nightmarish.

Once the full truth comes to light, you are as distraught as everyone else for Lauren Myracle, the author in the eye of the storm. But, at the same time, you are heartbroken because your special, once-in-a-lifetime moment was swallowed up in a controversy not of your own making. The national press and social media are all over the story, of course, but the title of your honored book scarcely comes in for a mention. Ouch!

Here’s the thing: the authors selected as this year’s NBA finalists in Young People’s Literature are as blameless in this fiasco as Lauren, and yet, in a very real sense, they too were harmed. How? In the midst of the firestorm that followed, their singular achievements were overshadowed, overlooked, and almost completely ignored. That’s just plain wrong.

I’m not going to rehash the details here. Everybody knows them already. Suffice it to say, grievous mistakes were made, and have been corrected, outrage has been voiced, copious amounts of mud have been slung, and apologies have been offered. It’s done. Now, let’s take a deep breath.

For the record, there were a number of extraordinary books that just missed being chosen this year, and each judge had a favorite title or two fail to garner enough votes to secure a place among the finalists. (I’m still in mourning over the loss of one of my faves. I fought for it right up until the very last vote!) But that is the nature of the beast. There were more than 270 books submitted for consideration, and there were only five spots to fill. We read, discussed, and deliberated over these books for four months, and we chose as carefully and thoughtfully as we could. The work was arduous, and the hours long, but we considered it an honor, and handled it accordingly.

Now, speaking as one of the judges for this year’s NBA panel on Young People’s Literature, I think—we all think—it’s time to shift the dialogue, and give some overdue, positive attention to the books selected. Here, then, are descriptions of the five finalists.

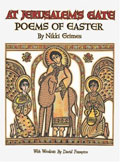

My Name Is Not Easy by Debby Dahl Edwardson

Set in Alaska above the Arctic Circle, My Name Is Not Easy interweaves nature, culture clash, religion and science into a vivid, multi-voiced narrative. The time is the early 1960s at the Sacred Heart Boarding School near Barrow. Eskimo, Indian, and White kids huddle at their own tables. Nothing is easy for kids uprooted from their villages: the food is not what they’re used to (where is the caribou meat, the whale fat?), the Catholic school rules are forbidding, the Cold War looms. This novel is deeply informed by the history and landscape of the high arctic region, where the relentless march of modernity presses on native culture. Back home the villagers still hunt, but now with the help of snowmobiles, not sleds. Though, as a wise elder remarks to a young hunter, “How is that snow machine going to find its way home in a blizzard?” This novel is deeply authentic; Edwardson lives where she writes, and she never falls into cliché. Even the nuns and priests are fully realized characters, with dilemmas of their own. This novel gives voice to an overlooked, outlier part of America, yet the dilemmas and victories of the characters are universal.

Okay for Now by Gary Schmidt

If you were fortunate enough to read the Newbery Honor book, The Wednesday Wars, you’ll be familiar with the main protagonist here. In the summer of 1968, Doug Swietek moves to a small town in upstate New York, which he fondly refers to as “The Dump.” Not that it would matter much where he lived, since he’d still have to contend with an abusive father, a delinquent brother who routinely mistreats him, while sorely missing the oldest, most beloved brother who is away in Vietnam. Desperate for inspiration, Dough clings to a one-time encounter with a baseball star in this tour-de-force. What are the stats? A town that offers up a literary dugout of eclectic characters with bite and wit: a librarian/art teacher, an eccentric playwright, past her prime, a feisty female friend who proves she is more, and a host of grandmotherly neighbors who show Doug was kindness looks like. Schmidt uses these, along with Audubon’s Birds of America, to layer a rich story about choice, inner strength, and the transformative power of art. In fact, this is the first work of fiction I’ve come across that actually takes the reader inside of the process of creating art, while allowing him to experience, along with the character, the wonderful ah-ha moments that comes with exploring the creative process. An additional element that made this book a standout was the prominent place of the library in this narrative. Altogether an amazing achievement!

Inside Out and Back Again by Thanhha Lai

Immigration was a recurring theme in the books we read this year but this one, which happens to be a novel-in-verse, was the clear standout. In a pure and authentic voice, a girl named Ha tells the story of her family’s harrowing escape from Saigon as it falls, the horrific ship-ride to America, and the other-worldly experience of landing in Alabama where the coldness of strangers awaits them. Ha, a tough and tender ten-year-old fights for her place in America while relying on the strength of the culture that gave her birth. The emotional impact of this story is felt as much in the words that aren’t said, as in the words that are. With hints of humor throughout, the poetry carries the rhythms of the Vietnamese culture. Readers will think more kindly toward the immigrants in their midst after spending time between the pages of this book. For me, this was love at first read!

Flesh and Blood So Cheap by Albert Marrin

This work of non-fiction explores the infamous Triangle Fire, one of the worst, and most preventable, work-related disasters in American history, eclipsed only by the events of 9/11. In the hands of Marrin, the scope of this story is deep, and wide. The book traces key points in the history of Southern Italians and Russian Jews—the primary victims of the fire—exploring the reasons their forebears immigrated to America, and what brought their descendents into the factory sweatshops of early New York. Readers learn about the so-called “Black Italians,” the impact of the Mount Vesuvius eruption, the Russian pogroms, the Pale of Settlement, right up to Ellis Island, once known as “the Island of Fears,” and the fall of Tammany Hall, illuminating bits of history connected to the Triangle Fire event. The book then follows the impact this disaster had on shifting labor laws and practices to create the more humane, and safe, working environments we all enjoy today. Mirren also brings to light unheralded heroes and heroines of the American Labor movement who rose up to lead reform, and organize unions to push for necessary changes in the workplace. There is drama, poetry, and music in the language here, allowing this history lesson to flow with ease.

Chime by Franny Billingsley

Don’t be fooled by the cover. There is nothing cookie-cutter about this novel. Take twin sisters, a boggy landscape, a handsome young stranger, a ghost or two, then add a magic cauldron, and stir. This book features some of the most lively, original, engaging line-by-line writing you’ll find anywhere. What’s more, the lush language is at the service of a story which manages to explore a dark psychological bond that will be eye-opening for alert, self-reflective readers, and heart-pounding for fans of romance in a kind of steampunk fantasy landscape. This book will be a stretch for many readers, but the remarkable use of language makes the journey a singular experience.

Now that you’ve had a chance to learn something about these outstanding books, I hope you’ll check them out for yourself. They are well worthy of your attention and the authors deserve all of our support. Just imagine, for a moment, if you were one of these authors.