The Problem with Poetry

For the record, just because a particular notion is repeated, over and over again, doesn’t necessarily make it true. The earth is not flat, nor is it the center of the universe. People of African descent are not intellectually inferior to the white race. And contrary to what you may have heard, over the years, from (well-meaning?) editors and agents, poetry can, and does, sell.

Pardon me if I presume to know what I’m talking about, but I am, in fact, sitting on a lovely sofa, set in a small, but beautiful home, paid for by a career built on writing children’s poetry and novels-in-verse. I believe that qualifies to say a thing or two on the subject, yes?

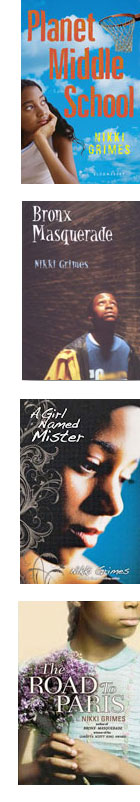

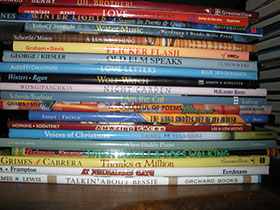

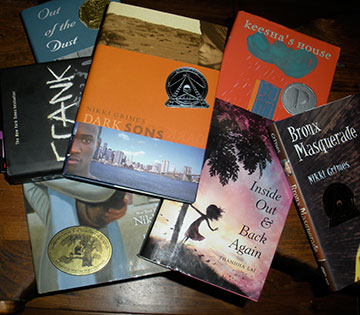

I recently spoke at a conference at which I heard it stated, unequivocally, that poetry doesn’t sell. When those words hit the air, I wanted to leap out of my skin. I’ve been hearing that old adage since I first entered this field more than 30 years ago. Had I, for a moment, taken that oft-repeated statement to heart, I’d have no career. The 50-plus books I’ve published, most of them children’s poetry, or novels-in-verse, would not exist. I would never have won the NCTE Award for Excellence in Children’s Poetry, nor awards for my body of work, or the ALA Notables, Coretta Scott King Award and Honors, or any of the other awards and citations my poetry has earned. None of it would exist if I’d believed that well-worn idea.

I recently spoke at a conference at which I heard it stated, unequivocally, that poetry doesn’t sell. When those words hit the air, I wanted to leap out of my skin. I’ve been hearing that old adage since I first entered this field more than 30 years ago. Had I, for a moment, taken that oft-repeated statement to heart, I’d have no career. The 50-plus books I’ve published, most of them children’s poetry, or novels-in-verse, would not exist. I would never have won the NCTE Award for Excellence in Children’s Poetry, nor awards for my body of work, or the ALA Notables, Coretta Scott King Award and Honors, or any of the other awards and citations my poetry has earned. None of it would exist if I’d believed that well-worn idea.

To be fair, if you are a poet, it is highly unlikely that you will become wealthy working in this genre, no matter how well you hone your craft. That much is true. But chances are, you already know that. I would wager that most writers, keen on this particular genre, aren’t looking to make a killing in the marketplace. They simply have a penchant for the lyrical line, and a passion for metaphor. Like me, they pen poetry because they, quite frankly, can’t help themselves. Poetry is in them. It’s part of their DNA. Poets don’t value their work in terms of fiscal weight, and that’s where we differ from agents and editors.

Agents and publishers are in the business of making money by selling books. We all understand that, although I wish interest in producing a rich and diverse variety of quality literature for the next generation, were more widespread. Still, we shouldn’t be surprised when agents and publishers push for vampire lore while the genre is hot, or discourage dystopian novels when they feel the trend is waning. Not so long ago, writers were dissuaded from creating books for teens, as there was yet no perceived market for them. That makes sense, right?

But. Aren’t we glad Judy Blume ignored the naysayers, back in the bad old days, and wrote novels for teens anyway? Aren’t we glad Jack Prelutsky and Shel Silverstein beat the poetry drum before verse was in vogue? Aren’t we grateful for Myra Cohn Livingston, and Eloise Greenfield, and Lucille Clifton, and Arnold Adoff, and a host of other poets who’ve enriched the lives of young readers?

I attended the first inauguration of President Obama, in 2009. One of my favorite moments of the ceremony was the reading of a poem. I love that poetry has played a part in inaugural celebrations of the past. Each time a poet has risen to that great podium it is a reminder that this genre has something substantial to offer. Poetry can provoke, challenge, disturb. It can soothe our souls, or spur us on to greatness. It can inspire, uplift, and make the heart soar. However, poetry can accomplish none of these things if it is not written.

I’m all for being honest with poets about the realities of the marketplace. I know that poetry, in the main, does not sell as well as prose. But it can, and does, sell. Is the field extraordinarily competitive? Absolutely. Is crafting quality poetry difficult? Of course it is. All good writing involves a huge investment of time, energy, and often, research. But that’s a lousy excuse for telling a gifted poet, who has a hankering for haiku, who eats and sleeps simile, who mires himself in metaphor that he or she should give up the very idea of penning poetry as a literary career.

Here are a few thoughts: the next time you come across a poet who clearly demonstrates a gift for this genre, don’t tell him to hide his light under a basket. Instead, tell poets to be smart about their choice of subject, to research the market to make sure their ideas haven’t already been done, to consider the needs of school curriculum and shape their work accordingly so that their books of poetry will be as marketable as possible. Encourage them to consider narrative books in verse—novels, biographies, historical fiction, creative non-fiction.

On the other hand, if the writer has no gift for this genre, tell him so. If his poetry is not topical, tell him that. If his poetry is not age-appropriate, tell him that. If you, personally, lack the know-how, or frankly, the interest in selling poetry, tell him that. But please, whatever you do, don’t tell a poet not to be a poet. That’s a bit like telling a leopard not to have spots!

One last thing: While poetry may, indeed, be difficult to place, it is not impossible. So please, please stop telling tomorrow’s poets that poetry doesn’t sell. If you do, you might as well tell them that New York Times bestseller Ellen Hopkins is a figment of our collective imagination; that Sonya Sones and Prince Honoree Helen Frost do not exist; that Newbery Honoree Joyce Sidman does not exist; that J. Patrick Lewis, and Naomi Shihab Nye, and Paul B. Janeczko, and Jack Prelutsky, and Sara Holbrook, and Jamie Adoff, and Tony Medina, and Marilyn Nelson, and Georgia Heard, and Marilyn Singer, and X.J. Kennedy, and Jane Yolen, and Margarita Engle, and Lee Bennett Hopkins, and Pat Mora, and Allan Wolf, and Gary Soto, and Eloise Greenfield, and Nikki Grimes, and a host of other working, publishing, award-winning poets do not exist. And that, my dears, simply isn’t true.

One last thing: While poetry may, indeed, be difficult to place, it is not impossible. So please, please stop telling tomorrow’s poets that poetry doesn’t sell. If you do, you might as well tell them that New York Times bestseller Ellen Hopkins is a figment of our collective imagination; that Sonya Sones and Prince Honoree Helen Frost do not exist; that Newbery Honoree Joyce Sidman does not exist; that J. Patrick Lewis, and Naomi Shihab Nye, and Paul B. Janeczko, and Jack Prelutsky, and Sara Holbrook, and Jamie Adoff, and Tony Medina, and Marilyn Nelson, and Georgia Heard, and Marilyn Singer, and X.J. Kennedy, and Jane Yolen, and Margarita Engle, and Lee Bennett Hopkins, and Pat Mora, and Allan Wolf, and Gary Soto, and Eloise Greenfield, and Nikki Grimes, and a host of other working, publishing, award-winning poets do not exist. And that, my dears, simply isn’t true.