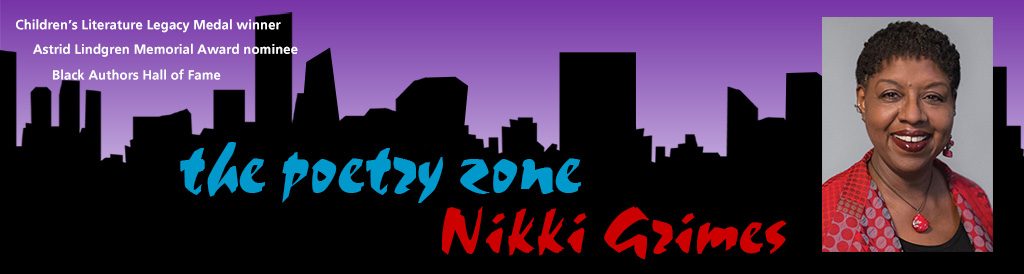

A Cup of Quiet: Tips for Long-Distance Sharing by Nikki Grimes and Cathy Ann Johnson

Nothing brings as much light to my eyes as the sight of a grandparent and grandchild playing hide and seek, or giggling between sips of imaginary tea at a tea part, or — best of all — curled up in a comfy chair, reading a book together. Who can argue with the beauty of that?

But, alas, not all grandparents are blessed to have their children’s children within easy reach.

What if you and your precious grandbabies are separated by distance? What if you live in a different city, or several states away? Or, what if you’re separated by an ocean? What then? How in the world are you going to connect? That’s a question that often occupies the mind and heart of illustrator, Cathy Ann Johnson, a question that most especially came to the fore as she worked on A Cup of Quiet, a book that celebrates the special relationship between a grandmother and her grandchild. This was a book Johnson longed to share with her own grandchildren. There was just one problem. Cathy Ann and her husband, Federico Conforto, make their home in Rome, Italy while her American-born children live in the United States. She couldn’t exactly pop in for an afternoon story-time.

Fortunately, Cathy Ann is not one to simply ponder a problem, or challenge. She’s driven to find a solution, and find one she did. Correction: she found several. I’ll leave it to her to share them.

Cathy Ann’s Tips

Here are a few ideas I’ve been using with my grandkids to share A Cup of Quiet during virtual visits online. These ideas are specific to the themes of this book, but the idea of creating games that tie in with the themes of other books should work, as well. Try these on for size, and see what other ideas they might inspire.

1. The Quiet Cut Craft Show

This is a sweet, hands-on activity where one or more children are invited to create their own “Cup of Quiet.” You can organize with parents ahead of time to help gather materials — markers, glue, construction paper, or even printable mug templates that we can make available for download. Have each child design a unique cup. Afterwards, have them present it, describing what their personal quiet feels like. Is it blue like the sky, green like the grass, or maybe yellow like sunshine? Next, invite them to share what their quiet looks like, smells like, and how it feels inside. It becomes a heartwarming moment of self-expression and connection.

2. Sound and Seek

My grandsons love a good game of virtual hide and seek, and Sound and Seek is a big hit. We take turns counting one-to-ten, then someone makes or plays a sound — e.g. a cat’s meow, the honk of a big truck, or the sound of running water. We listen carefully and try to identify the sound. Is it loud or soft? This game helps children notice the world around them with intention, and gently teaches them that quiet lives in the in-between moments, too.

3. A Hunt for a Cup of Quiet

This one is extra special. I hide little coffee mugs around my cozy Italian studio. With the iPad in hand, I take the boys on a virtual walk through my space. Their laughter bubbles up every time they spy one of the cups I’ve hidden. Every discovery becomes a new cup of quiet. With each cup, we pause, put our hands over our hearts, hold our hands over our heads then take a deep breath. What is the takeaway? It’s a treasure hunt for peace, and they love it.

4. Let’s Play in the Kitchen

We move our video screens to our kitchens, where we practice making our very own Cup of Quiet. Only this time, we fill our cups with something other than sounds. This time, we fill it with things found in our fruit bowls, refrigerators, or pantries.

“What’s in your cup?” I ask.

“My cup has strawberries,” one of them says.

“What color? How big?”

“I have mountain-sized strawberries in my cup,” Cairo, my two-year-old grandson, announces proudly.

“Nona, I want chocolate in mine!” he adds.

Then the boys help Nona imagine a very special cup.

“You need sugar!” one says.

“Is it white or brown?”

“White!” they both shout.

But Cairo insists, “You have to have milk, and it’s brown!”

Once everyone has their cup, we put our fingers gently over our lips and whisper.

“Shhhhhhh … be very quiet. We’re drinking our Cup of Quiet.”

There you have it — Cathy Ann Johnson’s tips for sharing our book A Cup of Quiet. So now, my friends, the question is, are you ready to share a special story time with the young readers in your life, whether near or far? Cathy and I are willing to bet your little ones are as eager as you are. I can hear them lick their lips, right now. Yum!