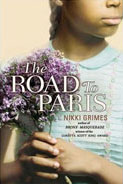

The Road to Paris

I spent several years in and out of foster care when I was a child. Little wonder, then, that foster children pop up in my poems and stories. I didn’t explore the theme in a fuller text, though, until I wrote The Road to Paris.

I spent several years in and out of foster care when I was a child. Little wonder, then, that foster children pop up in my poems and stories. I didn’t explore the theme in a fuller text, though, until I wrote The Road to Paris.

The Road to Paris is a novel about Paris Richmond, a young foster child who is separated from her only sibling, Malcolm, and sent to live in her next foster home, all alone. She has to come to terms with this difficult separation, and must struggle to find a place for herself in a house full of strangers. The novel explores that journey, and the strengths Paris develops along the way.

Of all the foster homes I lived in, myself, the last and best was in Ossining, NY. I chose that as the setting for much of The Road to Paris. And yes, I drew heavily from my own life experience in creating the story of Paris. There are wholesale differences, though. The number of homes Paris lived in, versus the number I lived in, is a perfect example. Before I landed in the good foster home, I had to survive half a dozen hellish ones. That was reflected in an early draft of the book. However, my editor strongly urged me to roll back that number to limit the bad experiences to one or two, and to move the story more quickly to the good home. I grumbled quite a bit, as is my want, but I eventually caved. I wouldn’t do that, today. Too much truth and authenticity was lost in the bargain.

One thing I definitely wouldn’t change is the ending. In it, Paris is faced with the choice to either return to the birth mother, who has already let Paris down in more ways than she can count, or to remain in the foster home, where she is well loved and cared for. Readers, yearning for the traditional happy ending, were rooting for the foster home. Paris, however, opted for her birth mother, risky though that choice might be. (Her mother struggled with alcoholism.) Notwithstanding, the choice Paris made is the choice I made, is the choice most children make. It is the choice that is true.

Several older readers have asked me about the tag line, “Keep God in your pocket.” I love that line, and it came to me in a moment of pure inspiration. I was looking for a non-intrusive way to express the element of simple faith that sustained Paris on her journey. I wanted something organic, yet something potentially powerful. After all, faith was a critical element in my own survival, and I thought it should be in Paris’s, as well.

I wrote The Road to Paris for all children, but especially for those struggling with problems outside of their control. They need to know that, despite their current circumstance, they can come out on the other side—whole, healthy, and happy.

Here’s one of my favorite passages from the book.

The next morning, Paris was on a platform at Penn Station, waiting for the train that would take her to her new foster home.

Paris’ heart beat so loudly, the noise filled her ears. For the first time, Malcolm’s hand was not at her elbow to steady her. His arm was not across her shoulders to calm her. His smile was not there to tell her everything would be all right.

The caseworker tried to hold her hand, but Paris snatched it back. She needed her hand to wipe away her tears. She’d never felt so alone in all her life.

Sometimes I wish I was like my name, thought Paris, somewhere far away, out of reach. Somewhere safe down south or on the other side of the ocean. Instead, she was neither Paris nor Richmond. She felt like a nobody caught in the dark spaces in between. A nobody on her way to nowhere.

The train rolled into the station, and she took one last look around before boarding, hoping to see her brother running to catch up.

Malcolm, Paris asked the wind, where are you?