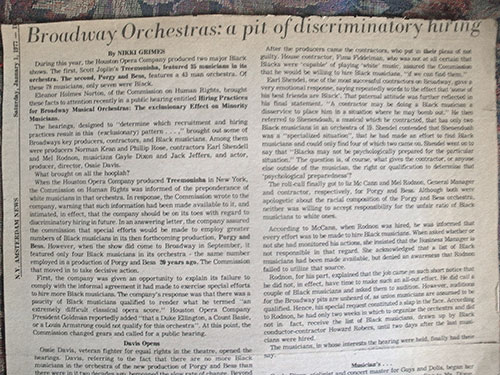

In preparation for a lecture I was giving on the use of poetic elements to enhance prose, I dug through a few old newspaper and magazine articles I’d written for sample passages in which I had done precisely that. In the midst of my search, I came across a piece of reportage from 1977 that had particular resonance. The title of the piece was “Broadway Orchestras: A Pit of Discriminatory Hiring,” and it was all about a lack of diversity in Broadway theater orchestras, discussed at a public hearing I was sent to cover.

“During this year, the Houston Opera Company produced two major Black shows. The first, Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha, featured 35 musicians in its orchestra. The second, Porgy and Bess, features a 43 man orchestra. Of these 78 musicians only seven were black.

“Eleanor Holmes Norton, of the Commission on Human Rights, brought these facts to attention recently in a public hearing entitled “Hiring Practices for Broadway Musical Orchestras: The exclusionary Effect on Minority Musicians.”

“The hearings, designed to ‘determine which recruitment and hiring practices result in this (exclusionary) pattern…’ brought out some of Broadways key producers, contractors, and Black musicians. Among them were producers Norman Kean and Philip Rose, contractors Earl Shendell and Mel Rodnon, musicians Gayle Dixon and Jack Jeffers, and actor, producer, director Ossie Davis.

“What brought on all the hooplah?”

Reading this piece gave me chills, for a range of reasons. For one, Ruby Dee, widow of the late Ossie Davis, had just passed. For another, the viola player Gayle Dixon, sister of friend and cellist Akua Dixon, was a personal acquaintance. Akua had just recently mentioned Gayle, who passed years ago. These twin facts were reason enough for my goose-bumps, but there was a third. The piece was about diversity or, more precisely, the lack thereof. In this case, it pertained to Broadway orchestras. These days, a lack of diversity most often pertains to children’s literature, a subject I have addressed on more than one occasion. Apparently I’ve been bumping up against, and speaking out about, this issue for quite some time.

I wonder about the state of Broadway orchestra pits today. It’s been a long time since I last followed up on the subject. I’ll have to get the skinny from Akua. As for diversity in children’s literature, well, in case you haven’t been keeping up, the stats remain pretty dismal. But this isn’t a piece about statistics. This isn’t even a piece about the dollars and sense of publishing and marketing a more diverse selection of books for an ever-expanding, diverse population of readers. Instead, I want to talk about the good of it all. What comes from sharing books featuring children of one race or culture, with readers of another? That’s what I want to speak to.

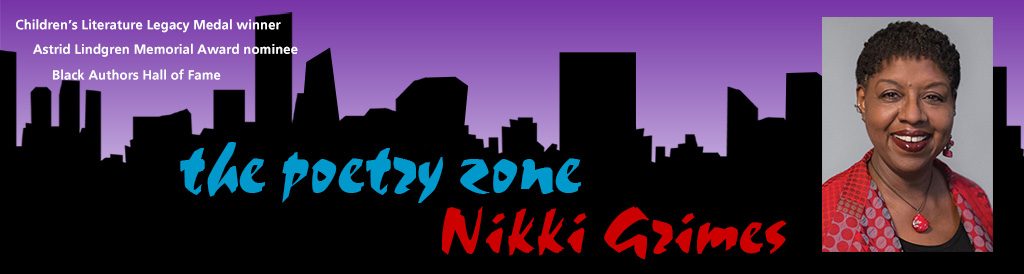

I know a thing or two about sharing children’s books across the color line, and not because I’ve taken polls, but because I’ve written and published more than 60 books since I entered this field, in 1977. Over that time, I’ve gathered hundreds of letters and emails from readers. I haven’t crunched the numbers, but I’ll wager that a significant percentage of them are something other than African American. Some are Asian, some are Latino, and many are white. How do I know that? It’s usually easy enough to judge from the name but often I don’t have to because the readers, unbidden, choose to mention their ethnicity. Yes, they write to tell me how they feel about my books, but also to introduce themselves. In the process, they share basic information about who they are: their names, ages, schools, grades, where they come from, and their ethnic backgrounds. Mind you, if we adults didn’t make such a big deal of the latter, these young people wouldn’t either!

I know a thing or two about sharing children’s books across the color line, and not because I’ve taken polls, but because I’ve written and published more than 60 books since I entered this field, in 1977. Over that time, I’ve gathered hundreds of letters and emails from readers. I haven’t crunched the numbers, but I’ll wager that a significant percentage of them are something other than African American. Some are Asian, some are Latino, and many are white. How do I know that? It’s usually easy enough to judge from the name but often I don’t have to because the readers, unbidden, choose to mention their ethnicity. Yes, they write to tell me how they feel about my books, but also to introduce themselves. In the process, they share basic information about who they are: their names, ages, schools, grades, where they come from, and their ethnic backgrounds. Mind you, if we adults didn’t make such a big deal of the latter, these young people wouldn’t either!

The notes and letters I receive from children and young adults across the country, and around the world, are very telling. Here’s what I’ve learned from readers:

They like humor.

They enjoy being moved and inspired.

Some have come to my books disliking poetry, but have come to love it. Many have since tried their hand at poetry, themselves.

Some come to my books as reluctant readers, but leave as avid readers.

They relate to my contemporary storylines.

They see themselves in my characters.

As for the color of my characters? Basically, my readers could care less. When they comment on race at all, it is only to explain exactly why race doesn’t matter:

Mariah T. says: “I’m white but to me race doesn’t matter, not one bit, and I’m reading your book Bronx Masquerade, and so far, I love it.”

Mariah T. says: “I’m white but to me race doesn’t matter, not one bit, and I’m reading your book Bronx Masquerade, and so far, I love it.”

Zach A. writes: “I think that if most of the characters in a book are not the same race as you, that should not stop you from reading it. That’s racist and just plain silly.”

Ary B. comments: “I stick my nose in your book, and have a hard time taking my nose out of it. I can put myself in your characters’ shoes and pretend to be them, even though I am white. I think African American authors should actually be recognized more, because it is nice to think that instead of assuming everyone is white, which white people tend to think, we are looking at the world in a whole new perspective.”

Can I get an Amen?

Unlike adults, children and young adults get it: the thing that matters most about a book is Story. And when readers are given the opportunity to dive into stories across lines of color and culture, they walk away with valuable lessons, such as:

- We are more alike than we are different.

- We all bleed.

- We all experience joy and laughter, suffering and pain.

- We all need love and blossom when we have it.

- We are all capable of both good and evil.

- What separates us is not our color, but our character.

We live in a country that, in word at least, celebrates its cultural multiplicity. Isn’t it past time that the books we share with our children reflect that, as well? There is only one right answer to that question, by the way.

We live in a country that, in word at least, celebrates its cultural multiplicity. Isn’t it past time that the books we share with our children reflect that, as well? There is only one right answer to that question, by the way.

If we live in a culturally diverse world—and we do—it behooves us to learn something about the cultural groups we live among. One of the least intimidating ways to learn those lessons is between the pages of a book. Yes, I’ve said it before, but it bears repeating.

As we in the diverse children’s book community like to say, let’s move the needle. This issue has been stuck on pause long enough, and it’s our children—Native American, Asian, Latino, African-American, and white—who are paying the cost.

2 Responses

I love both “Road to Paris” and “Planet Middle School” (the latter because I tell people “Look for my name.”) and have bought extra copies to give away. “Road to Paris” is a good book to give to someone who has or deals with Foster children. Most of your books, Nikki, cross ethnic lines. IT IS a pity that your books get neglected because they are thought to be ethnic stories rather then just plain human stories. They are often hard to find because of that. But I just found a copy of Planet Middle School and bought it. If I can let go of it, I might take it down to a Middle School nearby and donate it.

Your article brings back so many wonderful memories of African Americans working together to change/improve our life condition. The 2nd Human Rights Commission Hearing in 1976 was approx. 30 yrs. after the first one. I was so blessed to be at the 2nd hearing. Here we are 38 yrs. after our marching for our rights and “Everything Old Is New Again”. Orchestras rarely hire African American orchestral musicians. Most of the popular artists, black and white, also hire all white orchestras for their concerts. It’s as if we don’t exist.

My sister Gayle was a fantastic violinist, the last show she did was the Phantom of the Opera. Most pits have so few Black players that you never feel comfortable being there. There were several incidents that she refused to take and filed charges against her employers because of her working conditions.

Gayle was one of the witnesses at the hearing in 1976 that opened with Ossie Davis speaking.