The person currently occupying the White House has a penchant for spewing hate speech, as we have been reminded with his racist tweets suggesting that four outspoken Congresswomen, who happen to be people of color, should “go back to where they came from,” never mind that three of the four were, in fact, born right here in the U.S. of A, while the fourth, born in Somalia, has been an American citizen since the age of seventeen. POTUS’s racist comments, while familiar, are nevertheless disturbing. Worse yet, this particular speaker often refuses to own the words that have spilled from his lips five minutes after they’ve hit the air—unless, as in this case, he decides to double-down, which is a subject for another day.

As an author, I’m acutely aware of the power of words to heal or harm, to build up or tear down. I believe it’s imperative to choose our words carefully, and to own the words we choose, as well as the intention with which we use them. POTUS rarely does, of course. I wonder, though, how many others of us consider the words we use.

I’m particularly sensitive to the word “abandon,” or any of its derivations. I see it thrown around a good deal, these days, in connection with children forcibly separated from their parents at the border. To be clear, when a child is ripped from a parent’s arms, the parent can hardly be said to have “abandoned” that child. Yet, this is the language being bandied about.

I’ve noticed how frequently the word “abandoned” is attached to the commonly held narrative of the black father, and I wince every time. A man’s absence from a home is usually far more complex than that word would connote, especially if that man is black. His absence might be due to military assignment, work out of state, balancing multiple jobs, incarceration, or a contentious divorce. None of the above constitutes “abandonment.” No matter the reason for a man’s absence, he may, in fact, remain active in the life of his child without sharing the child’s home.

I’ve noticed how frequently the word “abandoned” is attached to the commonly held narrative of the black father, and I wince every time. A man’s absence from a home is usually far more complex than that word would connote, especially if that man is black. His absence might be due to military assignment, work out of state, balancing multiple jobs, incarceration, or a contentious divorce. None of the above constitutes “abandonment.” No matter the reason for a man’s absence, he may, in fact, remain active in the life of his child without sharing the child’s home.

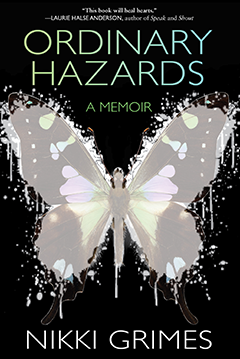

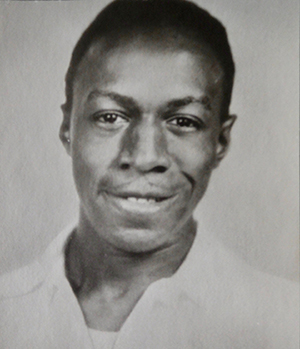

While writing my memoir, Ordinary Hazards, I had to address my own father’s periodic absence from my life. There were certainly moments, as a child, when I might have felt abandoned. But looking back, I know the label does not apply. My father’s absences were more complicated than that. He never gave me up, blocked me from his life, or left me with the intention of never returning. Nor was he ever emotionally unavailable. On the contrary, over the course of my childhood, he was quite present, and in critical ways. I would not be the person I am otherwise.

I called him Daddy.

It was my father who gave me my early arts education. He introduced me to the ballet, theater, and classical music. He escorted me to my first art exhibit, featuring artist Tom Feelings with whom I would one day collaborate on a book. My father signed me up for, and attended, my first poetry reading at thirteen. He was the person who exposed me to literature by and about writers of the African Diaspora. He took me for weekend jaunts to New Jersey and Washington D.C. He took me shopping for school clothes. We hit the occasional movie theater together and went for pizza runs during my weekend visits. Does any of this sound like abandonment? And yet, the casual observer, falling back on the common narrative of the absent black father would look at my story, note my father’s periodic absences and would say two+two = abandonment. Wrong.

We must carefully weigh our words and own them, whether we’re talking about absent African American fathers, or immigrant parents detained at our borders, weeping for the return of their children, or the Congresswomen of color who are full citizens with the right to serve their beloved country, regardless of the dark complexions and surnames that mark them to some as “other.”

It’s too easy for our narratives to casually be reduced to a few handy catch-words and phrases. When they are, we need to reclaim and reframe those narratives using language that encompasses the nuances of our truth. And we must do so over, and over again. It’s not a one-time proposition. Just ask the four Democratic Representatives targeted by the racist tweets from POTUS. This isn’t the first time someone has told them to go back where they came from and, sadly, it won’t be the last. Others will make false assumptions about them, and they will have to reclaim their narratives afresh, choose their own words and descriptors to set the record straight. And when they do, something tells me they will own their carefully chosen words, every single time.

One Response

Thank you! Thank you for sharing your story and your work with the world!